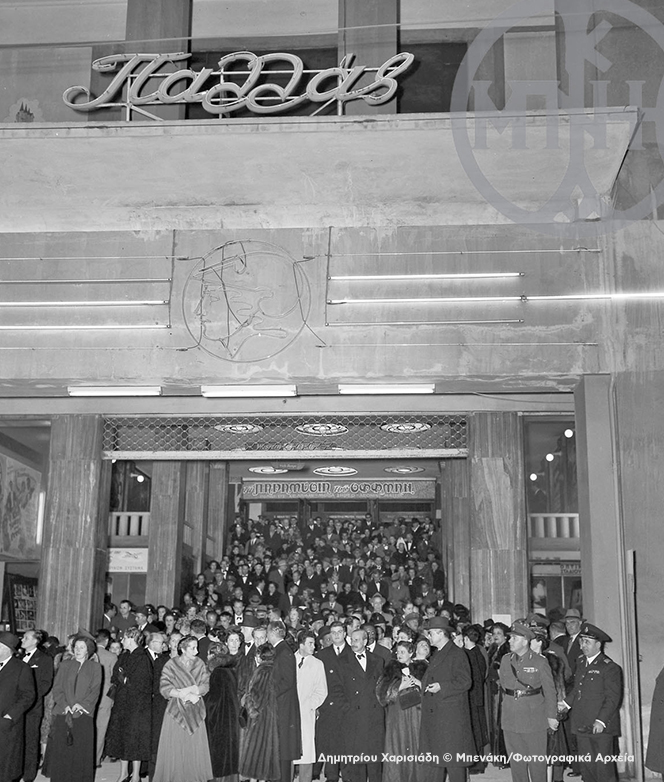

The intentions and enthusiasm of the era have been clearly documented: ‘…there will be richly appointed shops along the side of the arcade that will create the overall impression of a European passage… an extensively exploited basement with barber shops, bars, shoe shine stands, small shops, baths, a boxing and gym hall, a cabaret… The biggest movie theatre in the Balkans “a miracle of modernity and luxury… the latest trend in building aesthetics”!’

The decline of the Army Pension Fund building began in the 1970s. The crisis of cinema and the gradual change in consumer preferences affected the immediate surroundings and the building itself: the traditional quality hangouts faded away and people’s habits changed, shopping areas shifted, traffic conditions undermined old urban centres. The time had come to re-examine the future of the 60,000 square metres of workplace, shopping and leisure facilities in downtown Athens.

The first priority was technological modernisation, which transformed the old ‘Equity Fund’ into City Link, the current multi-purpose complex, fully equipped with all kinds of electromechanical installations; their volume alone, which is essential to support the project’s modern technological infrastructures, indicates the drastic change in requirements, but also the great challenges in the work of the experts.